I was fortunate to be able to visit Edinburgh Castle recently and as I was walking around learning about the history of the site, I couldn’t help but be struck by how well its history demonstrates the importance of the principles of war.

What follows is an attempt to highlight this with two specific examples from the castle’s history; the first is from the Scottish Wars of Independence (early 14th century) and the second is from the Elizabethan era following the forced abdication of Mary, Queen of Scots (late 16th century).

In both cases the castle fell. However, as they are separated by more than 250 years of military development- a period that included the widespread proliferation of the cannon- the path to victory in each varied significantly. Despite this, the principles of war as described in the Australian Army’s Land Warfare Doctrine-1 (LWD-1: Fundamentals of Land Power) can be seen (but with different emphasis) in each case.

But first some revision. The principles of war as laid out in LWD-1 (Army Knowledge Centre, 2016) are as follows:

1. Selection and Maintenance of the Aim

2. Concentration of Force

3. Cooperation

4. Economy of Effort

5. Security

6. Offensive Action

7. Surprise

8. Flexibility

9. Sustainment

10. Maintenance of Morale

11. Understanding War and Warfare.

In order to understand how the principles of war apply to each scenario, it is important to understand the political and technological context in which they occurred.

The Wars of Independence

The political cause of the Scottish Wars of Independence was the sudden death of the heirless King Alexander III (of Scotland) in 1286. Prior to this Scotland and England had enjoyed relatively peaceful relations, but this event set off a succession crisis in which many of the Scottish nobility put forth their claims to the throne. Unable to reach a resolution, the Scots decided to invite King Edward I of England to adjudicate. This resulted in John Baliol, Lord of Galloway being crowned King John in 1292.

In the years that followed Scotland drifted closer to France while King Edward I attempted to exert a degree of lordship over Scotland. This culminated when the Scottish nobility rebelled against the English interference and prompted England to go to war against Scotland (Yeoman, 2014).

Having captured Edinburgh Castle early in the war (1296), the English proceeded to hold it for the next 18 years until the Scots managed to take it back on 14 March 1314. This was accomplished by a small force of only 30 men under the command of Sir Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray (King Robert the Bruce’s nephew) (Yeoman, 2014).

This was a time before the widespread use of canons when the castle’s dominating position on top of Castle Rock (with its near vertical rock faces on three sides) coupled with its high walls and fortifications made a frontal assault extremely difficult.

Under the cover of darkness, the small force climbed up the north face of Castle Rock. After reaching the top they were able to scale the walls (completely bypassing all of the castle’s primary defences) and gain entry to the castle before the English defenders could reconcile what was happening (Yeoman, 2014). The small force was then able to exploit the confusion that the surprise caused to drive the English from the castle.

This was an approach that put particular emphasis on cooperation (to make the climb safely and undetected); security (to remain undetected until the critical moment); offensive action (the attack plan was bold; with 100% commitment to the offensive and no ability to turn back); and surprise.

The result was that the castle was captured in a single night with minimal bloodshed, remaining in Scottish hands until the end of the war.

The Lang Siege

The Lang Siege is the longest siege of Edinburgh Castle occurring from June 1571 until May 1573. The political catalyst for the siege was the forced abdication of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1567 and her subsequent imprisonment in England. This left an insecure throne, held by the infant King James VI (future James I of England). The siege itself arose after Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange resolved to remain loyal to Mary and to hold the castle in her name (Yeoman, 2014).

As cannons had proliferated throughout the 15th and 16th centuries (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2017) the castle was now well defended by up to 40 canons and trained gun crews (Yeoman, 2014). The besieging forces also now had canons which by the 16th century were capable of destroying medieval castle fortifications.

Despite this, through a combination of highly trained and disciplined gun crews, controlling the key and decisive terrain in support of a clear aim with high morale, the defenders managed to hold the castle for almost two years. However, by early 1573 Sir William Kirkcaldy only had nine experienced gunners left alive to crew the 40 guns (Yeoman, 2014).

Compounding the attritional toll was the fact that the besieging force had poisoned St Margaret’s well, effectively choking off the Castle’s water supply. This was a known vulnerability of the castle which lacked sufficient supplies of fresh water (Flannigan, 2014).

The siege was finally broken several months later when English reinforcements arrived bringing an additional 1000 troops and 27 canons. The reinforcements were sent into action on 17 May and Sir William Kirkcaldy surrendered on 28 May after the castle had been extensively damaged. (Flannigan, 2014)

For the besieging force the siege was ultimately determined through a combination of: concentration of force (delivering superior firepower at the critical time and place); cooperation (between the Scottish supporters of James VI and the English forces of Elizabeth I); security (the prevention of outside assistance reaching the castle); superior sustainment (the ability to draw provisions from the surrounding town while contaminating the castle’s water supply); and the understanding of the current state of warfare (being able to destroy the defences with canon fire rather than risk a frontal assault).

It should be noted though, that it wasn’t until a significant portion of the principles of war were in place that the siege was resolved quickly and decisively in favour of the besieging force. For most of the siege the defenders were able to hold the castle against superior numbers.

The two examples presented here serve to highlight how the principles of war can be applied to achieve the same result in very different ways depending on the technological realities of the day.

About the Author: Chris Bulow is an Australian Army engineering officer with experience in training, brigade maintenance and higher headquarters roles. He is currently posted to the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom where he is undertaking a Masters of Science in Explosive Ordnance Engineering. You can find him on twitter at @C_Bulow.

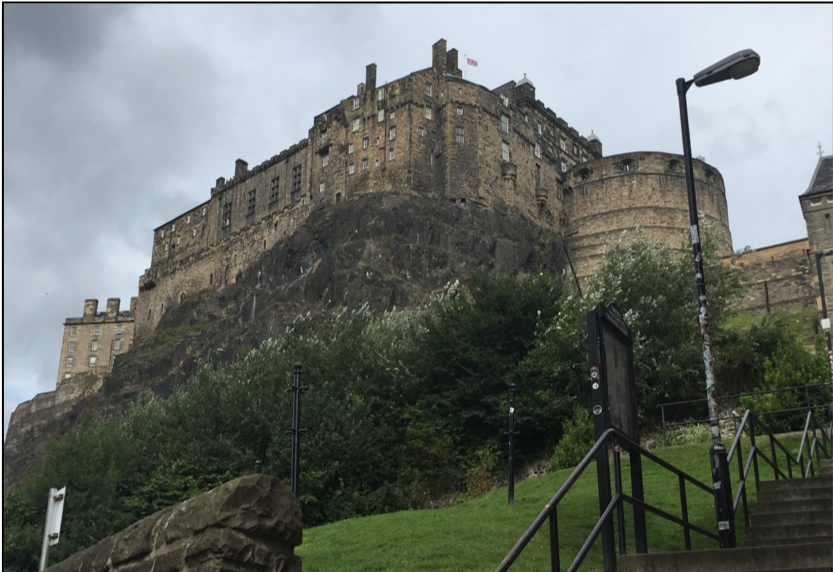

Feature Image: Edinburgh Castle as seen from the street below. The main approach to the castle is out of frame to the far upper right.

References:

1. Yeoman, P. (2014). Edinburgh Castle. Edinburgh, Scotland: Historic Scotland.

2. Army Knowledge Centre. (2016). Land Warfare Doctrine 1: Fundamentals of Land Power. Retrieved 13 Sep 19, from https://cove.army.gov.au/article/lwd-1-fundamentals-land-power

3. Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Cannon. Retrieved 14 Sep 19, from https://www.britannica.com/technology/cannon-weapon

4. Flannigan, S. (2014). Edinburgh Castle History – The Lang Siege. Retrieved 13 Sep 19, fromhttp://www.edinburgh-history.co.uk/lang-siege.html