The current social and economic crisis has seen record applications for enlistment into the Australian Defence Force (ADF) by skilled workers who have suddenly found themselves without regular employment. At the same time, the performing arts industry has suffered great losses due to closed venues and bans on live audiences.

While the new interest in military recruitment appears to be coming from the aviation and tourism sectors, those in the performing arts can also enhance the physical and cognitive edge required of modern military practitioners. In fact, we think that if you want to meet the kinds of physical and cognitive challenges military practitioners will face in the future, people with performing arts backgrounds may offer an underrated resource to the organisation.

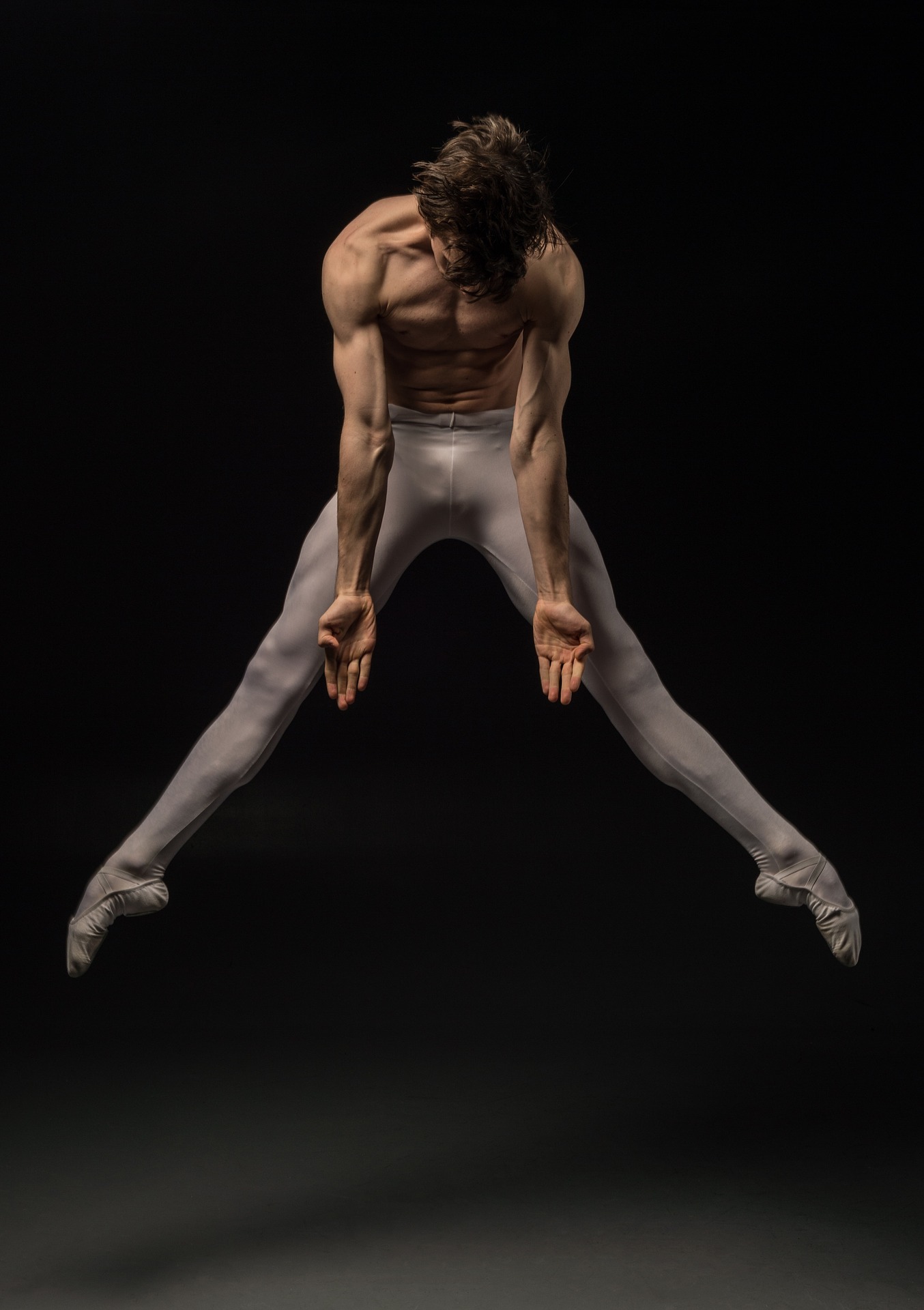

Performing arts have been gaining interest in military communities as part of veteran rehabilitation programs, but the performing arts build skills that, arguably, we would want in current and serving military practitioners. These skills include aspects such as bodily practice. Bodily practice, or ‘the reinforcing effect of repeated physical acts’, is evident in the military in the way problems are solved spatially with an appreciation of the physical strengths and weaknesses of each member of the team.

The military art and performing arts are similar in the way they combine the physical abilities of each team member to increase the total sum effect. The psychological effects of bodily practice to the opponent are an important part of military posture. People with performing arts backgrounds know how far they can push their bodies and come with a substantial knowledge of bodily practice.

Performers also use discipline in intensive training regimes. Individual and collective training (called ensemble in performance) require a foundation of disciplined practice. Whether the body is the instrument (in the case of dancers, singers, actors and acrobats), or a collaborator with the instrument (in the case of musicians, puppeteers and jugglers); the skills are based on a technical efficiency that requires focus and repetition.

While the performer is the interpreter of the creativity (the choreographer or composer), rather than the creator, they are still part of the creative process. However, performing arts can be more technical than artistic.

Performers possess a competitive mindset which cultivates emotional intelligence skills such as psychological resilience, persuasive communication, self-awareness and motivation. These are skills that are vital to fight in the ‘grey zone’ of current conflict and the multi-domain warfare of the future.

Perhaps in complete opposition to the above characteristics of discipline, single minded focus and bodily practice, the final reason that we believe those with performing arts backgrounds should be targeted for recruitment is diversity.

In his excellent book Range,David Epstein highlights that to truly succeed in a specialised world, it is more important to have a broad range of experiences. This should not come as any real surprise; after all, the majority of officers in Army are General Service Officers, who by definition, are trained generalists.

However, there is still a degree of homogeneity to the types of individuals who choose a career in Defence. By encouraging individuals with arts backgrounds to step out of their comfort zones and enter the military we are adding team members who will use a vastly different frame of reference to assist us to solve the wicked problems we are likely to face, improving both individual and collective decision making, and pushing the intellectual edge.

(Nick says, if you’re looking for an off the wall PME resource, have a look at the film Centre Stage. This is a surprisingly accurate portrayal of elite performing arts schools; where to succeed, individuals have to first overcome their own doubts, commit to mastery of their chosen path, and then traverse a complex web of relationships and maintain balance under pressure to succeed. Individuals who have this dogged drive to succeed are undoubtedly a benefit to any organisation. Cate says, watch Fame, which is a surprisingly accurate portrayal of her more gritty and street cred performing arts school at which dancers, actors and technicians learned how to work together in coordinated, technically synchronised and mutually supportive operations!)

The performing arts develops all these skills and more in its participants. Defence recruiting could do well by targeting people from the performance sector – performers, managers and technicians – to provide specialist capability for the future force. There are lots of opportunities to draw on the skills form this sector including:

- Weighting arts backgrounds in the same way as sport experience at recruiting.

- Designing recruiting campaigns that target those who do not fit the typical ‘warrior’ aesthetic (similar to the 2019 ‘Your Army Needs You’ campaign of the British Army).

- Offering short term service contracts to work in a specialist area offering technical advice.

- Calling for collaborative training which identifies new skills that enhance ADF operational effectiveness.

- Providing secondments for ADF members into performing arts organisations (from a business perspective) in a similar way to the business and government department secondments.

We are not suggesting there is a lack of creativity within the ADF, however at a time when recruitment is high and the arts industry is suffering, we could be targeting members of this community of practice, to enhance the future force. Bodily practice, discipline, competitive mindset and diversity are all useful qualities that people in the performing arts sector have in abundance, and that the ADF needs. We have made the move and there is no reason others cannot follow. Now may be the time to emphasise the other art of war.

About the Authors: Nick Alexander is a current serving Combat Health Officer, Communications Director of Grounded Curiosity and member of the Military Writers Guild. Prior to completing a Bachelor of Physiotherapy and joining the Army, Nick studied at The Australian Ballet School and performed with The Australian Ballet and English National Ballet Companies. You can follow him on Twitter @Nick_Alexander4.

Cate Carter is an Intelligence Corps Officer, PhD candidate and currently Managing Editor of the Australian Army Journal. She is also a former opera stage manager, having studied at the Centre for Performing Arts, Adelaide; and has worked in theatre, symphony, puppetry, rock and roll and circus. You can follow her on Twitter @catecarterarmy