In a time of increasing emphasis on the information domain, perhaps the words ‘See first, understand first, disseminate decisively’ offer a mantra for modern practitioners using information to wage war? The terms we’re accustomed to at the battlegroup and brigade tactical level are ‘information operations’ and ‘information actions’. These are taken to mean effects generated through and with information. To the operations officer, usually unschooled in these dark arts, they appear to state the same thing. Perhaps they might manifest in the mind’s eye as First World War leaflet drops in Europe that strangely became early twenty-first century leaflet drops in the Middle East. What does that say about the enduring quest for humans to decisively harness information or the intrinsic power of the written word? J.F.C Fuller suggests that moral and mental forces exert a greater influence on the nature and outcome of war, but they are inseparable from the physical. Information and its application in the operational art is offered here as the connector between them. The physical is enduring, but the mental and moral subjectively wax and wane in both an allied, civilian and adversarial sense. The operational artistry is perhaps seeing and understanding when the mental and moral are able to be decisively influenced and aligning the information effects as needed.

Coffee-break musings on the subject and a groundswell of interest among coalition practitioners offers opportunities to collaboratively cement a more cogent and widespread proliferation of what it means to use information in waging war. The sole caveat is this – it is not new. Sun Tzu’s wisdom of winning without fighting perhaps manifests as a renewed emphasis on information in a world where friendly casualties are an infrequent occurrence. These words may well reside in the minds of many already grappling with the subject of injecting informational effects into the forefront of the minds of operational planners to establish information as a ‘cognitive main effort’. What if the informational renaissance is simply a byproduct of western military strategies that have been unable to suppress, neutralise, or destroy (extremist) ideology in a physical sense leaving the informational ‘call for fire’ as the only conceivable method?

History offers examples of reformers who sought to harness the ‘secret sauce’ of their respective military institutions to confront the challenge of the day. The seven short years following the 1805 defeat by Napoleon at Jenna-Auerstadt allowed Gerhard von Scharnhorst to engender greater education within the Prussian military as a way to create stronger leadership. In 1865, Moltke the Elder renewed the same approach in bettering the General Staff planners to confront the realities of war with France and Austria ahead of the unification of the Germanic state. From 1919 Hans Von Seeckt sought to create an edge for the next war through doctrinal development to harness emerging technology amidst the restrictions of the post-Versailles world. General William DePuy and General Donn Starry sought a mathematical and technological approach to defeating the Soviet Motor Rifles in Europe after a decade of failing to defeat communists in Vietnam. Humans are intrinsically poor at recognising when a transition is occurring despite the efforts of military reformers. As a rule, the transition is more readily observed in retrospect. The military emphasis on the information environment and the efforts to integrate effectively may well be a reflection of the greater societal bent toward harnessing the content and flow of information.

In offering a new angle on something old, a traditional definition is often the start point. In this case, harnessing information simply implies influencing content and flow. Moreover, ‘information operations/actions’ or are simply those service or agency definitions the reader may presently subscribe to. A simple aim for all of the definitions offered here is to create a cognitive effect in the minds of the target based on influencing the informational terrain. That is to say, a target audience thinks, then acts in a way that is advantageous to the commander relative to the importance of the terrain on which they reside. With this notion in mind, influencing content and flow of information becomes the primary mechanism to affect adversary perceptions, decisions and actions in support of strategic ends.

The proliferation of the means to detect physical elements within the electromagnetic spectrum offers us a view on the ‘Battle of Signatures’ – that is the contest to reduce your own signature relative to the ability to detect another. Within the information environment there may now exist a ‘narrative signature’; that is a measurement on the strength of a narrative at a given point in time relative to the level of influence and measurable number of followers. The environment of cyberspace creates the ‘terrain’ upon which the narrative signature can exist – it is the generation of a form or contour of information characterised by clusters of users. Imagine shaping who holds the ‘informational high ground’ or contesting it with support from the informational ‘call for fire’. The Key Terrain of this domain is ‘usable information of value to the recipient’, the Decisive Terrain is critical information that allows ‘those who need it to take decisive action in any other domain’. Interactions may be viewed in a systemic sense through social media use to gauge reach and influence which could be clustered around the relative key and decisive terrain within cyberspace. The signature of this narrative situated in the informational terrain therefore offers a way to conduct targeting in the cognitive domain of the users.

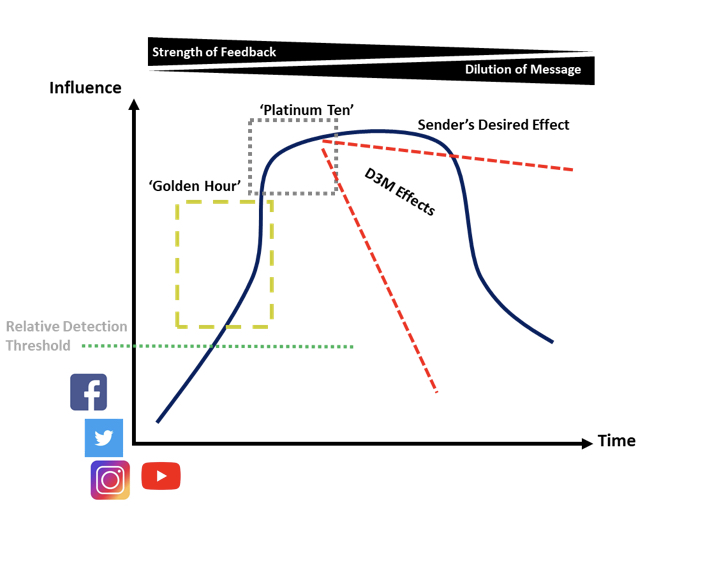

When considering the evacuation of wounded in combat, a common term to use is the ‘Golden Hour’ – broadly defined by surgical treatment in the hour. An enhancing factor in this time is the ‘Platinum Ten’ – stabilising the person thereby increasing the relative chance of survival. Medical officers everywhere will hold their faces in their hands in dismay at such a generalisation. The following discussion is also depicted graphically to aid in explanation. Consider the emergence of a narrative’s signature as the driving imperative to act in time to generate an effect. In terms of social media and its relative ability to generate a level of ‘hype’ or influence, the ‘Golden Hour’ represents the time to both ‘see first’ and ‘understand first’. In considering how to see in the information environment, the previously discussed information terrain (contours) and the clusters of users represent two such areas of interest. Designating those areas as key or decisive will support the subsequent ability to ‘disseminate decisively’. The ‘Platinum Ten’ is the window to act when understanding the rising influence rate of a given message to change the trajectory. This window is the place to make a decision to disseminate using a specific set of mechanisms.

Graph 1: The Social Media Bubble

In a modern conflict, authorities may be delegated to a one-star to drop a bomb, but the same informational ‘call for fire’ such as sending a tweet or uploading a YouTube video typically has permissions much higher. They are likely a function of trust and a relative understanding of the complexity in the political environment. In considering the effects that could be leveraged on the basis of both understanding the Golden Hour and effectively identifying the Platinum Ten, there are four options offered here for delegation. These options are to deny, dissuade, discredit, or manipulate (D3M). These effects can be aligned sequentially or concurrently to support actions in other domains.

To understand the D3M, we must understand the nature of the mediums. The fact is they are all hyper-connected and users can quickly post to multiple formats multiple times ensuring their post receives the most attention. Also, the overlap of platforms ensures the broadest possible dissemination of the message. For instance, one person may only have 500 friends on Facebook, but some of those friends are also on Twitter and some of those followers have a different group of followers on Instagram. A video posted on YouTube may not be on any other platforms, and this presents an opportunity to stop the influence before it flows to another medium. Also, it is important to note the focus of achieving effects is generally on the sender(s), receiver(s), message, and medium.

First, to deny a particular narrative or message is extremely difficult unless the sender(s) can be identified and targeted before they launch. Once a message enters the “Golden Hour” it is beyond the ability of any unit or organisation to deny. However, we can deny the receiver(s) from continuing to pass the message along through targeting the medium. Dening the user the ability to pass the message requires close partnership with media platforms to report and take down posts or videos (e.g. YouTube taking down ISIL beheading videos). This is critical, because a video may be posted to YouTube, but once it is passed over to Facebook or Twitter the rate of influence and sharing increases exponentially. Therefore, it is critical to deny the influence on the medium it was first posted on. Often the other platforms link back to the original, and if that can be denied, the effects will be achieved. Once identified, the sender could be targeted by brigade or task force organic cyber and electronic warfare capabilities. This would prevent further messages from emanating from that particular sender or group.

Next, the focus of dissuading is more heavily focused on effects on the receiver(s). Here it is important to understand the local networks and the influence of family and friends. In her recent article for Wired, Megan Molteni says “People are more likely to believe rumours from family and friends.” [1] If this is true, then those networks can be leveraged to dissuade the target audience from being influenced by or passing a message along. The effects of dissuading can be amplified when matched with specific actions to discredit.

If dissuading focuses on the receiver(s) then discrediting focuses on the sender(s) and the message. Local commanders and units have the means to discredit a message with their Public Affairs or Strategic Communications providing truthful and timely information. The critical factor is time, and this is where some innovative methods to leverage fact checking by using algorithms to increase friendly tempo in providing truth to counter disinformation.

Discrediting the sender(s) is slightly more complicated, but this is where layering information means is critical. Again, exposing the sender(s) with factual evidence of their lies can discredit and reinforce dissuading the receiver(s). On the other side of providing factual evidence and truth, is manipulating the message or information to further discredit the sender(s) and dissuade the receiver(s). Finally, manipulating the message, medium, sender(s) or receivers(s) is where things can get a little stickier. To achieve the desired effects the sender(s) and especially the receiver(s) cannot know the message was altered. Psychological operations (PSYOPS) and other clandestine or covert options require manipulation to reside at a higher authority level, mostly to ensure there is no stray voltage or “blue-on-blue”. However, as Carmine Cicalese discussed in his 2013 Joint Forces Quarterly article “The planner’s lesson learned was to develop a bold yet feasible plan and then seek the authorities…” [1] So, planners and commanders at lower echelons should not bemoan a lack of authorities to manipulate. Instead, they should develop plans and request the authorities. Another option is to develop a playbook or consider likely scenarios where a message needs to be manipulated, like plotting on-call targets before a patrol, which would allow the commander to make a call and request the authority based on a pre-planned target scenario.

When will we realize the tempo of operations in the information environment has outpaced the hierarchical targeting structure? Something is amiss when it requires more “star” power to achieve effects with non-kinetic means than kinetic. If we understand the network ecosystem, we can identify a video on YouTube and counter message it before it gains momentum on Twitter and Facebook through leveraging organic capabilities at the lower echelons of military command working on concert with national and civilian leaders. The “Golden Hour” and “Platinum Ten” require effects of D3M delegated and senior leaders to accept risk by trusting their subordinate commanders or holding them accountable.

[1] Megan Molteni, “When WhatsApp’s Fake News Problem Threatens Public Health,” Wired, (9 March 2018) https://www.wired.com/story/when-whatsapps-fake-news-problem-threatens-public-health

[2] Carmine Cicalese, “Redefining Information Operations,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 69 (National Defense University: 2d Quarter 2013): 112.

About the Authors:

Von Lambert is a mechanised infantry officer studying at USMC Command and Staff College, attending the School of Advanced Warfighting in 2018. He spent his regimental time in the 7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment. He enjoys a glass of South Australian red wine in his spare time whilst pondering the character of the next war. Tyler Quinn, USMC, is a military police officer and a fellow student. He is plank holder of Ender’s Galley, a community of interest focused on the information environment, dedicated to the art and science of war. Follow @endersgalley or @tc_quinn07