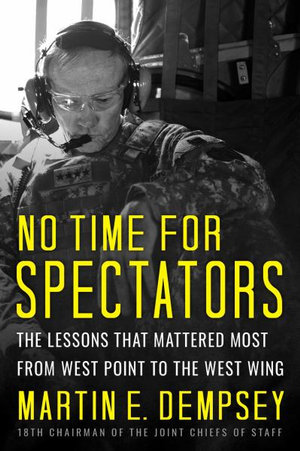

On the third page of the introduction to Martin Dempsey’s latest book I knew I was onto another excellent and timeless look at leadership from someone who has lived and breathed the effects of it across the span of his outstanding career. As such, I also knew I would need to set an alarm to tell me stop reading and go to bed. At the allocated time, and now fully engrossed, my alarm went off and I promptly turned it off, made a pot of tea and settled back down to finish the book. Needing an extra couple of cups of coffee the next day seemed worth it.

Through his honest and humble vignettes Dempsey doesn’t just talk about leadership but proves it through offering stories to his readers that don’t just demonstrate his own, and to most unattainable, level of excellence; he also highlights his own failures at every level throughout his career. From being yelled at by senior Cadets at West Point to being delivered a ‘teaching opportunity’ in a meeting by US President Obama, Dempsey tells us when he needed to be better and shows that our journey of learning never ends.

Of the nine distinguished chapters in Dempsey’s book, and the many ancillary lessons described throughout the process of highlighting his key lessons learnt, those that resonated with me the most were understanding followership, understanding loyalty, being brilliant at the basics (or in Dempsey’s words “sweat the small stuff”) and never stop learning. These lessons are not new at all and I have learnt them over the years through my own mis-steps or through the counsel of much more senior commanders, however books on leadership should not teach you how to lead, just act as a friendly reminder.

The requirement to work hard at being an effective follower and knowing how to support others both up and across is often a forgotten factor when discussing leadership. Dempsey explains this well throughout his book from a myriad of different situations. “Leading up means being attuned to the challenges of those serving above you. It means working to be clear and concise. It means giving advice that might stretch beyond your current responsibilities. It means being honest and humble.” Being a good follower is in many cases a lost art, as we judge and criticise our commanders instead of enabling them. Retired Australian Major General Krause, AM once said ‘your headquarters will never be fit to command you’. This saying has stuck with me for many years and has rung true time and again, however instead of apportioning blame to a higher head quarters or commander, good leaders need to understand how to follow and ‘lead up’.

In connection with knowing how to follow is knowing and understanding the concept of loyalty. “Up to the point where decisions are made, it’s important for leaders and followers to understand that disagreement isn’t disloyalty. One of the leaders’ most important responsibilities is to establish an environment in which that distinction is clear to everyone”. Understanding that once the decision is made it is now an order and therefore the commander demands and deserves loyalty when enacting and disseminating the decision as if it is your own is the responsibility of every subordinate. My first exposure to a commander analysing the concept of good and bad loyalty came from an ex-Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Schurmann when I was his Adjutant and was running some junior Officer PME, whereby he simply stated ‘If someone is appealing to your sense of loyalty, they are usually doing the wrong thing’. Although this was more in the context of unacceptable behaviour, it opened the door for me to think a little more critically about the concept of loyalty in general.

As a junior leader it is incredibly easy to be carried away in the many things you simply have to know, from every conceivable historical conflict to the current geo-political climate. The ex-Commander Forces Command, Retired Major General McLachlan, AO once stated that a junior leader needs to have a ‘deep and narrow’ foundation of which they can then begin to build a wider understanding of the operational and strategic picture. This concept f being ‘brilliant at the basics’ is not a new concept and is further enhanced through Dempsey’s definition of ‘sweat the small stuff’. Knowing and understanding the minutia of the job that you are doing enables you to be prepared for when bigger things inevitably come along. “It is reinforced in the little things we encounter in life, so that it is prepared for the big things that will inevitably challenge us.”

The biggest lesson I took away from this book was that we are all learning. The day we stop investing in our own development and as a result, investing in the organisation, is the day we need to look for alternate employment. In this career, there are ‘no time for spectators’.

I would highly recommend this book to leaders of all rank levels. Reading about leadership not only helps to understand many lessons of the art through other people’s experience, but it gives us an opportunity to reflect on our own similar mistakes throughout our careers and remember the small and often forgotten lessons that our commanders, peers and team members bestow on us through their own performance. This book is written in a simple and relatable way that afforded me the opportunity to think back on my own brief decade of service and how similar many of my own errors have been, compare my reaction to the problem with that of another and as a result, how to better react to similar situations in the future.