This is the second article of a series on the Twelve Urban Challenges. You can access the series here.

Urban conflict presents 12 challenges, as introduced in the previous article. The first two of these are matters of perception and there is a puzzling contradiction between them. On the one hand there are clear and accelerating trends towards urban conflict and on the other a longstanding phenomenon of dissonant understandings of such operations.

The proposition that ‘the future fight is urban’ is supported by extensive analysis of robust trends, broad agreement in the literature and appears in most armies’ doctrine. Yet this theoretical recognition of an emerging and acute problem does not translate to significant capability choices, acknowledgement of the brutal nature of the fight, nor adequate recognition of the different objectives of enemies.

This article examines these two attitudinal challenges to set the scene for later articles discussing the complicated challenges of physical structures and the overlying complexities generated by the population and politics.

Challenge one – Escalating Stakes and Risks describes the trend towards more frequent and larger scale urban operations driven by urbanisation, conflict within these growing areas and adversaries seeking physical and political “cover.”

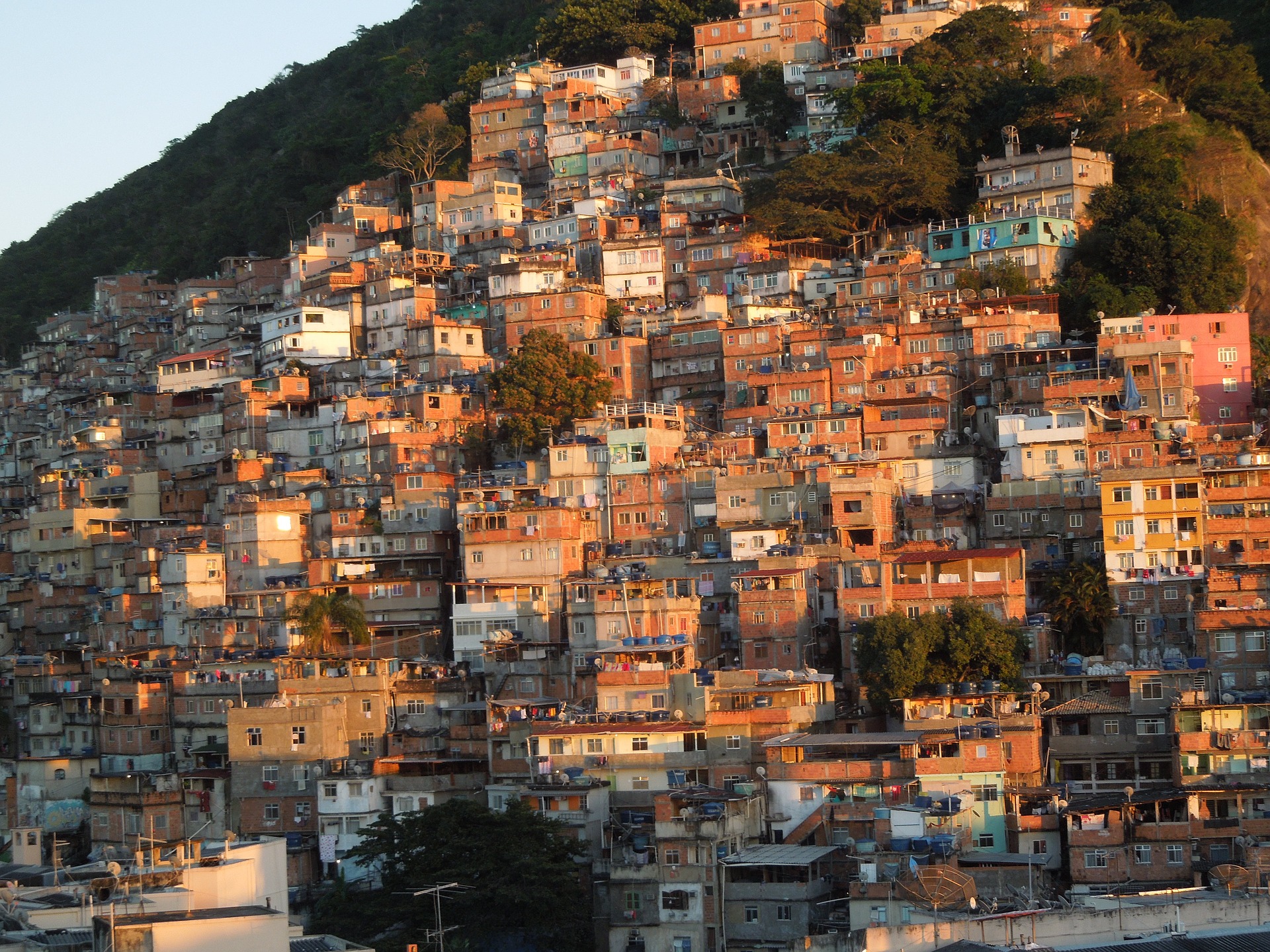

In 500BC Sun Tzu counselled that “the worst policy is to attack cities” because of the cost in blood and time. Although armies may wish to heed that advice, increasingly they won’t get a choice. Worldwide urbanisation is spreading over what once was space for manoeuvre, small armies disappear within vast contemporary urban conurbations, while conflict within these growing cities is increasing. Above all, adversaries have learned that they can move into cities where there is both physical and political cover from the technological might of the West.

An urban seize, defy and discredit strategy confronts governments with unpalatable political alternatives: allow an adversary to flout the state or fight them where the costs in blood and destruction are potentially prohibitive. These three trends – as illustrated in Figure 1 – are the major factors driving urban conflict, with community conflict and adversary exploitation flowing directly from the unequivocal urbanisation of the planet.

Importantly, for forecasting purposes, these trends have been both foreshadowed, observed and reported on for several decades, not only by military and strategic analysts but by international bodies such as the UN and ICRC, who have been increasingly highlighting the humanitarian consequences. There is remarkably wide consensus that urban war is globally increasingly probable and militarily and politically problematic, with negligible evidence or argument to the contrary.

Increasing global risk and stakes is the first and great urban challenge. Militaries do not dispute this forecast, but most appear to believe that they can avoid or minimise their involvement in such war. This leads to the next challenge – that recognition of risk has not translated to its mitigation.

Challenge two – Dissonant Beliefs is the phenomenon of nearly a century of cognitive disconnect between the foreseeable demands of urban battle and military preferences and policies. The shortfall is observable in the tension between:

- Broad acknowledgement of the inevitability, difficulty and possible scale of urban operations and risk-accepting absence of systems to reduce casualties and political risk in intense combat.

- The primordial demands of urban combat operations and the expectations of liberal societies.

- Military focus on tactical methods and outcomes whilst adversaries target strategic perceptions.

The fight for cities is central to the history of war, except for a hiatus in 18th and 19th century Europe, and this is further discussed below. City fighting re-emerged in the 1930s as first the Chinese and then other armies learned the defensive potential of urban areas against armoured warfare. Since then, combat in cities has become more frequent, had greater strategic significance and is increasingly overlaid with complexities of population and politics.

The puzzle is why for almost a century, armies around the world have ignored the experience of others and prepared themselves remarkably little, if at all, either to attack or defend on substantial urban terrain. When unable to avoid such fighting, militaries have either not changed their capabilities, or temporarily changed them and then reverted: lessons are painfully learned and promptly forgotten. Norms of open country warfare dominate, manifested in various ‘dissonances’.

A pattern of ‘capability dissonance’ or disconnect between a widely acknowledged increasing probability and difficulty of the urban fight and military attitudes to fielding appropriate tools for that fight is a widespread and enduring phenomenon. Only Israel and Russia, two countries that suffered politically significant losses in urban fights in recent decades, have fielded significant quantities of equipment focussed on combined arms urban operations.

Israeli procurement explicitly reflects the domestic political need to minimise military casualties and an international political need to limit civilian casualties, emphasising armoured protection and engineer systems. Formations assigned to the urban fight are equipped with the tank-based Achzarit and Namer APC for the infantry but also very heavily protected bulldozers, small numbers of specialist armoured engineer vehicles with innovative modifications such as front access hatches, as well as a variety of mechanical tools and munitions for breaching as well as ISR robots.

In contrast, the Russians have emphasised firepower for the urban battle and lethal UGV. Their TOS-2 T72-based multi-barrelled flamethrower can fire a salvo of 30 x 220 mm thermobaric rockets whose enhanced blast detonation can crush or asphyxiate everyone in a small city block. Also based on the T72 is the BMP-T, intended for urban infantry suppression using twin 30 mm cannon and machineguns. For the close battle, there are dedicated detachments of Chemical Troops, in their own specialised tracked vehicles whose assault task is to employ their handheld launchers to precede any assault with a thermobaric round through every window, or alternatively use incendiary smoke munitions to deny the building.

Other Western armies have rarely acquired platforms dedicated to the urban fight, and then only last-minute purchases such the D30 bulldozers bought by the US from Israel in preparation for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Perhaps even more perplexing, specialised (but not-urban specific) post war versions of platforms that had proved valuable in street fighting during WW2 (such as armoured engineering vehicles with 165mm demolition guns) or systems that proved their worth in urban fighting in Vietnam (such as the ONTOS six-barrelled anti-tank vehicle), were retired without replacement.

It is unsurprising that armies choose not to invest in systems for environments which they judge possible but unlikely – such as arctic warfare for Australia. It is curious that they do not do so for urban war when not only academics, but the doctrine of Australia, NATO and allied armies all say it is increasingly likely, difficult and a combined arms fight. Given that the army is configured for the most demanding type of operation – conventional war, it is strange that it does not equip for the most difficult form of that war.

The phenomenon of capability dissonance is not only manifest in procurement choices. It can be seen in the training realm. One example is the ‘non-learning’ of the technique of ‘mouseholing’. In 1846 the Mexican defenders of Monterrey in buildings shot down US troops advancing in the streets. The latter could not progress till they learned to knock holes through walls. Two years later during the Milan uprising, Marshall Radetzky’s Austrian troops made the same discovery. The technique has been ‘rediscovered’ every few decades by different armies in different theatres from China in the 1930’s, to Italy in the 40’s, to Vietnam in the 1960’s, but even when it appeared in doctrine, it has rarely been practised in training.

The Philippine troops clearing Marawi in 2017 were merely the latest to learn on-the-job. A wider pattern of training oversight is evident from the neglect of other historically proven all-arms urban techniques such as intimate direct fire artillery support, AFV close assault techniques and smoke screening.

There is also ‘expectation dissonance’ between a post-Vietnam perception in Western liberal societies that conventional warfare can be the surgical contest their armies espouse and aspire to wage – and the brutal character of the urban fight. Ironically, the problem may arise because of military success in delivering a largely sanitised representation of ‘precision conflict’. The (now academically challenged) belief that that war was lost because of the ‘CNN effect’ has motivated Western militaries, since the 1991 Gulf War, to develop effective media control and co-option mechanisms – leveraging an largely uncritical mainstream media in the post 9/11 political environment.

The result is Western norms that expect not just the proportional and discriminate use of force mandated under IHL but a level of restraint that is not. Similarly, popular media portrayals of Special Forces and Police operations reinforce tactical models of surprise and surgical precision. Many conventional militaries eagerly adopt these methods – regardless of their suitability for an intensive fight – and discount historically proven all arms close combat methods using tanks and armoured engineers.

Arguably, the consequence of a Western military ‘public relations’ success in portraying ‘restrained’ combat is that their troops are more likely to be committed to the fight with constraints that dictate an attritional infantry-focused approach.

The usual pattern of launching an army into a city fight in the last 15 years has been that they initially suffer casualties from IED and ambushes outside of buildings, over a period of days they adapt to wage brutal close combat with light weapons, then after heavy casualties shift the political climate, tactics change to emphasise systematic explosive destruction. This is an example of failing to do what Clausewitz said was the first thing in war – determining the kind of fight you are involved in.

Even should militaries be properly prepared to conduct the kinetic urban fight there may be ‘purpose dissonance’ between the military objectives of the fight they are conducting and the political factors. This is not new: political considerations drove the Germans to exhaust themselves and eventually become trapped at Stalingrad. The key point is that in contemporary urban fights, the attacking forces may not have the luxury of focussing on the military objective of ejecting the adversaries.

The latter may be entirely resigned to eventual physical defeat, but measure success in terms of a contest of narratives. In Marawi, this demanded the Philippines military not simply prevail in the kinetic fight but actively counter the adversary’s story, promote a government narrative of sacrifice and effective application of violence. Influence operations included video recordings showing Philippine troops immediately after being wounded, or when recapturing buildings and killing ISIS-Maute – sometimes shown in near real-time.

Overall, there is a pattern of dissonant understanding of urban operations. We can look back over thirty years and many armies and see a pattern of doctrinal acknowledgement of an historical and theoretical need that has not translated into dedicated capability decisions – in a way not apparent in other combat environments.

There is a dissonance between the observed practices of urban combat in recent decades and its restrained representations in popular culture and training paradigms, and similarly there is dissonance between the tactical fight our militaries concentrate on and the messaging that interests are enemies. What can explain these gaps? The next article will explore the psychology involved.

About the author: Dr Charles Knight researches capability for operations amongst populations and structures at UNSW and CSU. He has a practitioner and unconventional warfare background, served in the UK military and other armed forces, wrote the Australian urban doctrine and as a reservist is the SO1 Urban Operations at the Australian Army Research Centre. Views expressed are his own.