Generating, Expressing and Implementing ideas – A Framework

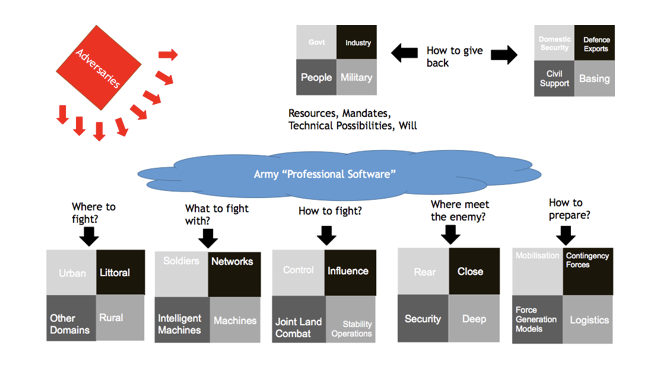

Part 1 of this blog ordered the terms strategy, concepts and defined big ideas. It analysed two “big ideas;” Army in the 21st Century/Restructuring the Army and Airland Battle and devised a system model. This model is shown at figure 1 and aims to show the minimum number of related factors that “big ideas” treat. The model is illustrative rather than exhaustive. It shows the breadth, depth, and interrelations of the problem. It reminds idea generators that: change in any part of the systems influences all other components; all change is viewed through the Army’s existing professional software; and the value of change in the system measured by the potential effect on an adversary and by industry, the other services, government, and society. It also reminds us that adversaries operate across the system, not just against fighting echelons. It is a model, and like all models, it is incomplete, for example, it doesn’t reflect cost, training and education and doctrine that influence all quadrants. This model serves as basis for further discussion in part II.

Figure 1: System Model for Big Ideas

The second part of this series synthesises problem solving theory, the observations from practical experience and change management principles. This leads to a framework for big ideas and illustrative examples of how the model can be used. Principles for complex problem solving are not universally agreed, but the design method provides a useful start point. Seven pillars for thinking about complex problems proposed by Smith in Design and Planning of Campaigns and Operations in the Twenty-First Century are repurposed here as problem solving guidelines. These pillars are compared with change management principles from Force Design in the 1990’s analysis of Army in the 21st Century (A21), and a third and practical prism developed in part I. Figure 2 shows the three methods banded into five themes.

Figure 2: Characteristics of complex problem solving, change management and case studies

The five themes relevant to the generation, expression and implementation of big ideas that emerge from figure two are:

Theme 1 – Think divergently/Develop options. The model shown at figure 1 can be used to guide divergent thinking and identify space for action. Figure 2 shows an indicative example of how it governs an idea for change in the environmental focus of Army by visualising the current state, the future state, and some ways to transition that vary in cost and difficulty.

Figure 3: Example Ideas for Change within a Quadrant

Alternatively, the model can guide whole of system change. A common innovation is to use the waste products from one part of a system to enhance another. For example, at Gatwick Airport leftover food is processed and burnt and the heat used to generate power. Another innovation method is test, model, test to iterate products, for example, a new iPhone is produced annually or biannually. Figure 3 illustrates how creative thinkers might use these ideas to develop new linkages between parts of the system.

Figure 4: Example – Change the relationship between Quadrants

Theme 2 – Time, Iteration and Adaption. Feedback drives the adaptive process and allows risk to be managed. Battle laboratories, centres of excellence, field training, and simulations provide feedback. The creation of new centres oriented on machine-human teaming, urban or littoral operations, or advise and assist missions, might support Army’s ability to iterate quickly.

Theme 3 – The Role of Institutional Leader. Colin Gray’s maxim that the “political context is the principle driver of wars incidence and character” applies equally to anticipated war as it does to the present or past. The institutional leader has the acutest sense of the political context and is vested with the authority and resources to direct change and champion ideas. The institutional leader ensures that big ideas are not preyed on by committees and institutional biases. This principle does not invalidate methods where the institutional leader natures and promotes bottom up approaches.

Theme 4 – Use narrative – explain how the Ways and Means deliver the Ends. The big idea is a story, it starts in the current state and follows the plot to a new and better state. The story must hold the logic, illustrating that the ways can use the means to deliver the ends. Like poetry, this story must reflect what the reader already knows and speak to their worldview. The story must also be complete, explaining the costs and risks inherent in making change within the system. Unexplained tension, cost or risk will fester and weaken the narrative. Constructing, testing and refining this narrative is central to the implementation of the big idea. This might require digital media skills and knowledge that Army does not currently possess.

Theme 5 – Develop change tools/Have early successes. Change needs tools: these reinforce narrative; program professional software and inform option development. These tools can also be a success in themselves, offering low risk options to indicate the direction of travel in times of uncertainty. Airland Battle and A21/RTA invested in systems to evaluate options and measure success or failure. Army 21/RTA used a trial Brigade and Defence Science Operational analysis team. Airland Battle used a trial Division and incorporated emerging concepts into Corps, Division and Airforce exercises.

This post set out to articulate a framework for the generation, expression, and implementation of big ideas for the Australian Army’s future. Five relevant themes emerged. First, big ideas demand divergent thinking to generate ways that are sympathetic to the characteristics of the system. Second, the institutional leader is central to the big idea. Third, iteration and adaptation are essential for the big idea to take shape. Fourth, the organisation should express the big idea as a narrative that explains ends, ways, and means. This narrative must be transmitted and amplified through the physical and virtual domain, by both “doing” and “showing.” Five, change needs tools: these reinforce narrative; program professional software and inform option development.

————————————————-

About the Author: James Davis, the Australian Army Liaison Officer to the United Kingdom Land Forces, is the primary author of this post. It was informed by discussions with Sergeant Matt Wann, a UAS operator working with Future Land Warfare Branch and Major Scott Holmes who is a Chief of Army Scholar studying the impact of the fourth Industrial Revolution on Military Affairs. These discussions took place during a recent visit to UK industry, science and military groups concerned with Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, Autonomy and Robotics.