A problem of Just War Theory is that most governments who engage in military action assert their cause is just, but what about when it is unjust? Is the role of individual soldiers merely to practice jus in bello (how combatants are to act in war) and leave jus ad bellum (whether to go to war) to their political leaders?

Roger Bergman provocatively argues that an answer to the unjust war tradition where ambitious or misguided leaders start wars that are not ethically justifiable is selective conscientious objection (SCO) – the right and responsibility of soldiers to refuse to engage in unjust conflict. His Preventing Unjust Wars is thought-provoking in three main ways: examples of heroes of selective conscientious objection; concerns around moral injury when soldiers engage in unjust action; and principles for teaching conscience and moral identity.

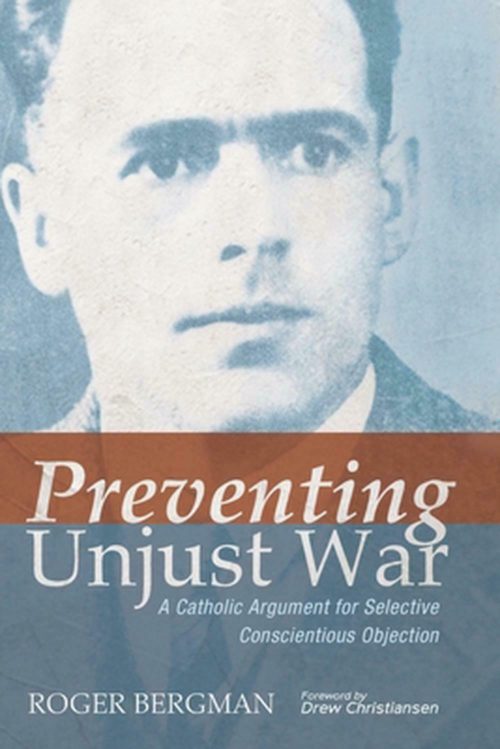

The book opens with the story of Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter refusing service for Nazi Germany. He was not a pacifist nor highly educated. Yet after enlistment and during military training, he recognised Hitler’s evil ambition and listened to his conscience. He refused to let any sense of nationalism trump his values. He believed it was better to suffer unjust death than to inflict it. So he was executed “for undermining military morale” – and later recognised as a martyr by Pope Benedict XVI.

Bergman acknowledges the majority position, supported by Saint Augustine (AD 396-430), Shakespeare (Henry V, 4.1) and most military forces, that soldiers do not have responsibility to judge their country’s war in which they fight. But he also examines the ethical teaching of scholastic philosopher Saint Thomas Aquinas (AD 1225-1274) and others who elevate the role of conscience, albeit with the need for conscience to be informed. It was fascinating to read of a Turkish unit who surrendered to the Russians on the moral grounds that their war was not legitimately declared according to Islamic law. It is also significant to read that Germany now allows for freedom of conscience and SCO. This is no surprise after the fall of Third Reich and realisation of a “mass slumber of conscience”. So German officers who refused certain orders in Iraq or requested exemption from using certain weapon systems in Afghanistan had their critically minded discrimination accepted.

Bergam’s commentary prompted me to reflect on how Australian Army training instils respect for legal orders, yet also responsibility for not following illegal orders. When faced with unethical conduct, we want soldiers who say with moral courage: “This is not what we Australian soldiers do.” Recruits need the discernment and language to be able to express concerns in non-insubordinate ways. Inculcating the practice of respectful contributory dissent is part of ethical leadership development (cf. “Developing Army Leadership into the Future”). Thus case studies of those German officers could be a useful addition to Australian Army leadership training.

This line of reasoning may be troubling to leaders who wonder where it could lead. But inviting soldiers to evaluate the justice of conflicts is a check against unjust war and enhances will and moral courage for a just cause. As John Howard Yoder comments, albeit as a pacifist: “A people and an army assured that they will not be asked to fight unjustly will fight with undivided courage and therefore more successfully” (cited in Bergmnan, p.119).

After making heroes of selective conscientious objectors, the second take-away was that moral injury can be most acute in soldiers forced to engage in unjust war. Bergman illustrates with examples from Skakespeare (Henry IV, I:2:3 from Shay Achilles in Vietnam), obliteration bombing in WWII, military sexual trauma in Vietnam, enhanced interrogation in Iraq, graphic violence that drone pilots view, and lack of respect for local citizens shown by occupational forces. His integrated definition of its causes and affects is:

“Moral injury in warfare is caused by a betrayal of what’s right by legitimate authority or an individual’s perpetrating, failing to prevent, witnessing, or learning about an incident or its aftermath that violates deeply held moral beliefs and expectations, especially the right to life and respect for human dignity. It presents an enduring and debilitating anger, guilt, and shame.” (p.86)

Good soldiering is important for Army’s reputation, ethical stance and to provide reflection on morality. That resulting anger, guilt and shame can become not just emotional responses but enduring states of mind. When soldiers cannot justify their fighting as moral and worthy of a cause they can believe in, it is an easy step to feel trust betrayed and be left with unseen lasting wounds.

The third value of the book is to prompt rethinking how to teach conscience and moral identity. Training soldiers for war’s dilemmas and when and how to contribute to the orchestration of lethal force deserves best practice efforts. Bergman helpfully reviews relevant psychological development literature on how young adults develop rational thinking and moral identity. He unpacks the key role of self-reflection, peer interaction, principled reasoning, perspective-taking, virtue ethics, empathy for the dignity of all, and the principled thinking underlying the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Bergman writes as Professor Emeritus at Creighton University where for two decades he taught on Christian Ethics of War & Peace and Morality of War Seminar. He reflected on his experience of inviting students to grapple with the “ill-structured problem” and defend a reasonable solution of whether Christians are not allowed under any reason to kill, or whether there is sometimes justification. His students use a workbook on conscience and evaluate case studies of WWI, WWII, Vietnam and Iraq. One student reflected: “Never have I been made to think harder in a rigorous format about a crucial, relevant, and personal moral issue … I literally lost sleep over deciding my ethical standpoint … a paper that causes one to question one’s assumptions, beliefs, values, and opinions is the definition of a good personal ethics paper” (p.153). This is the level of not just intellectual thinking but moral identity I am convinced we need to cultivate as a learning community in the next generation of Australian Army recruits and trainees.

About the Author: Chaplain Darren Cronshaw is a member of the Part-Time Army serving in 2021 at 1st Recruit Training Battalion, Kapooka and then back to Army School of Transport, Puckapunyal. For civilian work he pastors Auburn Baptist Church and teaches leadership and research methods with Australian College of Ministries (Sydney College of Divinity).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Army, the Department of Defence or the Australian Government.

**If you found any of this content distressing and would like to talk to someone, there are a variety of support services available to you:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Open Arms: 1800 011 046

ADF Chaplaincy Services: 1300 467 425 and ask to speak to your area on-call Chaplain