History must be studied in breadth, depth and arguably most importantly in a proper context, not least because conflict is essentially between societies or elements thereof.

Air Commodore Peter W. Gray[i]

Despite the broad acknowledgement of military history’s utility in Professional Military Education (PME), there is a tendency to focus overwhelmingly on the ‘big battles’ from major conflicts. While western military history is often the focus of discussion and critical analysis, post-colonial African conflict provides fertile ground for observing the varied manifestations of warfare’s myriad elements. Sadly, this rich learning opportunity is often disregarded, or considered through overly-simplified critical lenses, which add little to robust discussion.

Framing these conflicts through monocausal schema, such Robert Kaplan’s ‘new-barbarism’[ii] or Mary Kaldor’s ‘new war’[iii] paradigm, has resulted in a perception that African events are perhaps not worthy of our time when placed alongside famous battles such as Hamel, Kokoda, Maryang-San, or Long Tan. This attitude disguises the complex underlying factors that are a part of post-colonial African conflict and substantially representative of the contemporary (and likely future) operating environment.

There can be little doubt of Africa’s ascending importance in international affairs, particularly conflict. Joe Kobuthi’s[iv] recent article highlights the reemergence of great power politics in the African continent and, alongside concerns of exacerbating transnational terrorism, serves to reinforce the validity of a closer study of African conflicts. While it remains important to extract lessons from Australian and western military history, the study of post-colonial African conflict presents numerous lessons from the application of Combined Arms Warfare to a greater understanding of the causes and consequences of conflict at all levels of war. This article offers two texts and one case-study with the intent to prompt inquiry into a seemingly-ignored aspect of military history.

Almost two decades on, Anthony Clayton’s Frontiersmen: Warfare in Africa since 1950[v] continues to provide an informative compendium of case studies focused on understanding the conduct of post-colonial African warfare. Frontiersmen’s focus on the specifics of warfare establish it as an excellent starting point for selecting case-studies pertinent to desired key themes. While Clayton does a relatively paltry exploration of the underlying themes of African conflict, the depth of detail in the conduct of various campaigns on the continent establishes Frontiersmen as an excellent introductory text.

Contrastingly, Paul Williams 2016 War & Conflict in Africa[vi] thoroughly examines the driving forces of warfare in Africa and provides a conceptualisation of conflict drivers likely to influence future conflicts beyond Africa. Williams offers a ‘culinary’ approach to analysing warfare that has much to offer by enabling a more precise visualisation of the unique aspects of various conflicts. Independently, these texts provide excellent starting points for an inquiry into post-colonial African conflict.

Together, these texts establish a comprehensive overview of the various causes, conduct, and consequences of warfare through an African lens. While these elements vary in relation to the diverse conflicts that have occurred throughout Africa, it is worth noting that a historical analysis of the aforementioned three Cs (causes, conduct, and consequences) can strengthen an understanding of current events. Such is the case with the Horn of Africa.

The Horn of Africa is one of the most volatile regions in the contemporary international environment. Developing adequate resolutions have been made increasingly complex by lack of governance, growth of transnational terrorist groups, and enduring state competition. The genesis of such complexities can be identified by an observation of key events in the Horn of Africa.

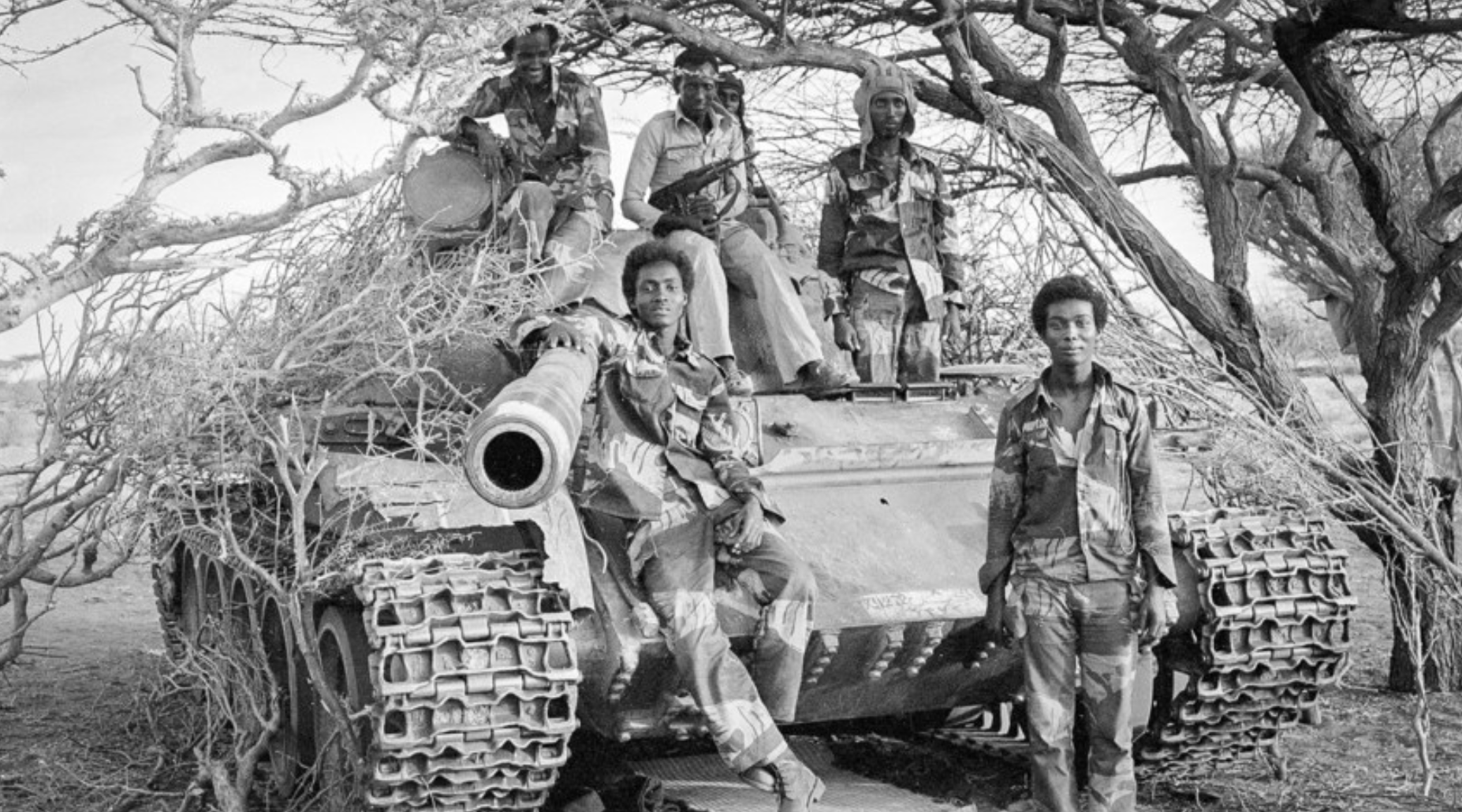

Analysing and discussing the conduct of the Somali-Ogaden war highlights many of the ‘ingredients’ that have shaped African conflict — such as inviolable but porous borders; shifting great-power alliances; and seasonal movement of agrarian communities. This conflict is a strong starting point as it contains several lessons in the application of combined arms and in doing so overcomes the stigma of African warfare as irrelevant.

There exist a plethora of similar case studies; however, this article merely seeks to propose the Somali-Ogaden war as a useful entrance into African conflict analysis, due to its ability to contextualise broadly-discussed contemporary issues.

Paul Williams highlights the utility of studying African conflict in asserting that a focus on Africa:

challenges some of the standard conceptual frameworks used by the students of contemporary war. Not least, it raises difficult questions for the trinitarian view of warfare popularized by Carl von Clausewitz’s unfinished classic On War. African cases often blurred the distinctions between Clausewitz’s central categories of the government, the military, and society.[vii]

As the impact of progression from nation to market state and the fourth industrial revolution is debated, critical analysis of post-colonial African conflict has much to offer in the realm of professional military education.

About the author: James Easton is an Australian Army Officer currently completing postgraduate study at UNSW@ADFA.

[i]Air Commodore Peter W. Gray RAF (2005) XII. Why Study Military History? Defence Studies, 5:1.

[vii]Williams, p. 5

[ii]Robert Kaplan, The Coming Anarchy, The Atlantic Monthly, Vol 273, No. 2, 1994.

[iii]Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organised Violence in a Global Era, Polity Press, 2012.

[iv]https://www.theelephant.info/features/2018/01/25/back-to-the-future-africa-and-the-new-cold-war/

[v]Anthony Clayton, Frontiersmen: Warfare in Africa since 1950, London, UCL Press, 1999.

[vi]Paul D. Williams, War and Conflict in Africa, Second Edition. Cambridge, Polity, 2016.