We do not rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.

—Archilochus, Greek soldier and poet

Introduction

Like other sub-units, Artillery Batteries operate in a chaotic, dynamic environment categorised by competing priorities and deficiencies in human resources. In the past, a systems approach to categorising and prioritising training requirements has not been sought, and subsequent training delivery has been sub-optimal. Such training is decentralised, unstructured, and not designed to achieve specific training outcomes—the training methodology is reflective of, and subservient to, the environment.

In the short term, these trends undermine sub-unit efficiency and effectiveness, while also resulting in unreliable sub-unit performance in the field. In the long term, uninspiring training degrades solider morale, subsequently affecting retention, manning, and performance. Additionally, the absence of a corporate knowledge management system means that positive training activities cannot be consistently passed onto incoming appointments due to posting or discharge.

Solution: A New Training Construct

During my time as Fire Support Officer, I have developed a ‘Training Construct’ designed to alleviate some of these shortfalls in contemporary training practices. I refer to it as a ‘system of systems’ due to its multi-faceted design, and its implementation is governed by a set of principles explained below.

Construct Components

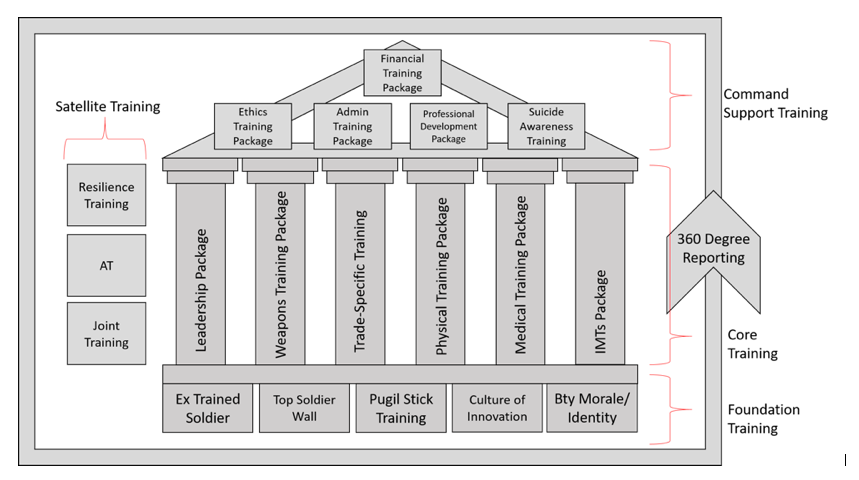

The Construct is divided into two components: the visual training package construct, and the corresponding package document. Initially, the sub-unit’s training priorities—derived from command directives and forecasted exercises—are established. This determines the general types of training that need to be addressed, as well as any other training priorities determined by sub-unit HQ.

A training package document is then created for each package which defines the specific outcomes, competencies, and resources associated with that package. This process solidifies the sub-unit training intent, transforming the concept into a physical document which is accountable and adaptable. Moreover, documentation of the training approach and useful resources makes the training replicable, forming the basis of the corporate knowledge retention system.

To facilitate effective training, a sub-unit’s culture must first be established. This is achieved at the ‘foundation level’ of the Construct, which specifies the activities and systems adopted by the sub-unit to generate the Commander’s desired culture. These may be physical objects like the ‘Top Soldier Wall’—cultivating a competitive, ‘will to win’ mentality—or specific activities like themed boozer parades to foster sub-unit identity. Once the parameters for foundation training are set, HQ can then determine what ‘core competencies’ they want their soldiers trained in. Trade training will always occupy this space, with the remaining elements prioritised by HQ.

Finally, the top of the Construct consists of ‘command support’ training, which aids in the sub-unit’s efficiency as opposed to tactical effectiveness. In the example provided above, this is where basic administrative training, as well as personal and professional development, nests. These elements can be directly aligned to unit-directed proficiencies (such as equipment husbandry), or areas of welfare that members of HQ feel strongly about and desire to see in the training program (such as suicide awareness). The construct is in essence a visible depiction of the sub-unit’s training priorities and how they interrelate.

Principles

The construct itself, however, is merely a visual means of conveying how training is categorised and organised. In order to achieve effective training, implementation of the construct relies on the series of principles explained below.

Accountable package masters. A key lever that supports the organisation and conduct of training is the allocation of accountable package masters to each training package. These package master position are filled by officers and SNCOs with considerable subject-matter expertise in that area—experience enabling them to design training that is of a higher standard than what might be achieved if the training officer were solely responsible for the task. The package master ensures the training package document is current, and coordinates large-scale training activities relating to their package. In this example, the Battery Guide is the trade training package master, as his role as the trade and equipment specialist makes him ideal to advise the training officer in the development of trade-specific training. The use of a package master disperses the workload throughout key members of the sub-unit and makes training recordable and replicable.

Outsourcing training to SMEs. A key component of the construct’s implementation is the leverage of external SMEs to implement specific training outcomes. Thus, to conduct a sub-unit medical training day, liaison with the Brigade medical unit is conducted. Similarly, should the sub-unit wish to provide financial education, this is coordinated through Defence-approved financial advisers. This principle has a number of implications: primarily, the sub-unit receives training from the most qualified and current source available. This process also disrupts the repetitive training that soldiers typically receive, exposing them to different capabilities and personnel within the Brigade, making the training more engaging and better-received. Engaging other units also establishes positive relationships throughout the Brigade, increasing the networking ability of the sub-unit’s officers and SNCOs. Finally, the utilisation of Brigade assets to facilitate sub-unit training promotes a positive sub-unit and unit image.

Active and reactive feedback loops. The final principle underpinning the Training Construct is continual feedback. Incorporating active (Innovation Drop Box) and reactive (360 degree reporting) feedback loops ensures flexibility and enables the continual improvement of the training program. The use of both active and reactive feedback loops provides soldiers with an unrivalled level of interaction with their HQ. The Innovation Drop Box enables soldiers to submit feedback/ideas at any time as a means of active adaptation to sub-unit training. Additionally, the sub-unit utilises a modified version of 360 degree reporting to conduct a bi-annual analysis of the organisation’s key processes, procedures, and leaders. This generates trust, flexibility, and inculcates a culture of mutual respect.

Conclusion

The Training Construct is a structured approach to training design and implementation, underpinned by a set of principles governing its effectiveness. While the structure and priorities are designed by sub-unit HQ, individual packages are owned by accountable package masters who can tailor effective training and be held accountable for its content. This centralises organisation while decentralising delivery in a way that delegates responsibility to, and imparts ownership on members of the sub-unit. Where possible, training is outsourced and delivered by external SMEs from within the Brigade or organisations within the Defence community. This ensures training is accurate, and also fosters relationships between units in the Brigade, ultimately generating a positive sub-unit and unit image. Finally, an Innovation Drop Box and bi-annual 360 degree reporting cycle promotes an environment of professional critique and mutual respect. These feedback loops enable the constant improvement of the training process, as well as sub-unit conduct in general.