Military history is often seen as the go-to resource for military professionals to learn about and understand their trade. It is full of examples that help us understand the profession of arms. However, as MAJGEN Mick Ryan, Commander Australian Defence College, points out, this may not be enough in an age of accelerating change. We will need new tools to help us prepare for the possibilities of the future.

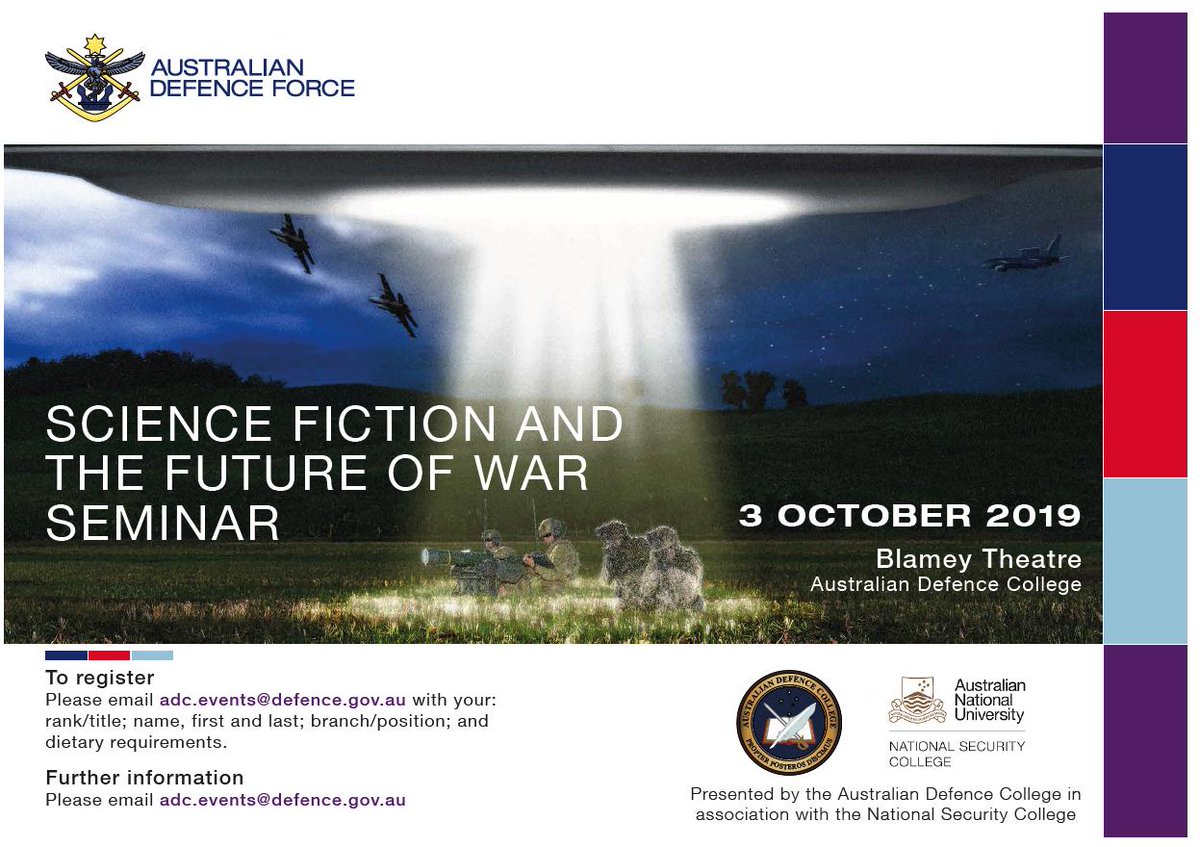

The inaugural Science Fiction and the Future of War seminar was an important step in developing new and inventive tools to aid in the study of war. Science fiction can compliment military history and enable readers to explore war, technology and civil-military relationships.

The seminar was opened by John Scalzi, an American Hugo Prize winning science-fiction author known for his series Old Man’s War (and for liking pie). Scalzi used six foundational titles[1] to go through a brief history of military science fiction, before delving into the assumptions, realities, strengths, and weaknesses of science fiction as a genre.

Scalzi’s key point was the importance of understanding science fiction as a simplified way to look at the world. Doing so can allow science fiction to explore the unforeseen consequences of specific scenarios and issues. He also emphasised the need for diversity among science fiction writers (including background and gender), in order to harness wide ranging perspectives that bring new insights and solutions to the problems of the future.

The first panel focused on the role of science fiction and its ability to act as a lens into future war. Authors Dr Janeen Webb, Dr Jack Dann (both award-winning Australian authors) and John Scalzi provided their perspectives.

Webb spoke about the success of science fiction in predicting the future, and noted that science fiction’s predictions of the future are always rooted in and underscored by present issues, biases and beliefs. There is a feedback loop between science fiction and reality where one can spark change in the other.

Dann emphasised that science fiction is a ‘projector of possible futures’ rather than a ‘predictor of the future’. Drawing parallels to Sir Michael Howard, Dann stated the aim was not to ‘get it right’ but rather to avoid getting it ‘too wrong’. Senior leaders in Defence can use science fiction to inform purchases and capability, and junior leaders can use it to prepare for possible future lived experience.

Speaking again on the panel, Scalzi described science fiction as a ‘controlled lab experiment’ used to demonstrate potential outcomes of a scenario, allowing science fiction to collectively demonstrate possible trends for the future. In a similar vein to Dann, Scalzi said that “the point of science fiction isn’t to get the future correct. It’s to provide a plausible vision of the future you can use to think about the future.”

The second panel featured Dr Russell Blackford, a Conjoint Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Newcastle; Professor Brian David Johnson, an applied futurist at Arizona State University; and Dr Cat Sparks, an Australian author with a PhD in science fiction and climate change.

Blackford started with a history of science fiction’s successes and failures in warning about future threats and dangers. He also spoke on the role of science fiction as an ethical reminder of the risks, costs and consequences of war.

Johnson introduced his work on threat-casting[2] and science fiction prototyping. This highlighted the challenges of communicating future threats to wide audiences and his solution was using comics to overcome this.

Sparks spoke about the role of human’s biases, and language in the development of technology. She focused on three main areas: the likelihood of humans developing robots in our own image and having to live with the consequences of that; our cleverness, but lack of superintelligence, as decision-makers; and how conversations about technology and ethics are often humans talking to humans.

This branched into a discussion around the strength of human versus artificial ethics, the bias inherent in all data, and the challenge of developing the ethical norms and culture that surrounds the use of future technologies.

Australian author John Birmingham, CEO of the ANU Cyber Institute, Dr Lesley Seebeck, and MAJGEN Ryan participated in the third panel. John Birmingham opened with comments about the relationship between science fiction and reality, and creativity and surprise. He went on to challenge ideas of security by describing how an indirect approach by an adversary targeting our food supply network could cripple many advanced nations. Seebeck spoke about the weaknesses and strengths of science fiction, highlighting the limitations of the simplified perceptions used by science fiction while espousing its ability to imagine and explore new scenarios.

MAJGEN Ryan proposed the idea of the ‘other trinity’[3]: organisations, ideas, and technology. Regarding organisations, he observed that science fiction can offer a pathway to organisational change and provide a means of exploring new force structures and concepts. On ideas, he noted that historically they have all been human, but we are now entering a period when technology can contribute to the generation of new ideas.[4]

This culminated in a panel discussion about the need to develop technology in step with ethics and values, to have both civilian and military investment in military change, and to involve business and academia in solving tomorrow’s problems. This emphasised that all problems are fundamentally human problems, less so technology problems.

The final presenter was Associate Professor Nathaniel Isaacson, who spoke about Chinese science fiction. He observed the adversarial nature of Chinese science fiction in relation to the West, particularly in rebalancing colonial relations. His presentation then moved to China’s use of science fiction as part of its overarching strategic narrative, and to China’s efforts to ‘own’ global science fiction as a means of soft power.

In closing this wrap up, it is critical to look beyond the traditional and accepted methods when thinking about the future. MAJGEN Ryan closed the seminar with this: “to understand and solve the problems of the future, we must have and engage with diverse ideas and people.”

About the Author: Officer Cadet Chris Wooding is a trainee officer in the Australian Army. He is currently at the Australian Defence Force Academy studying a Bachelor of Science, majoring in Mathematics and Computer Science. He has a strong interest in military history and the evolving nature of conflict and the profession of arms.

[1] ‘War of the Worlds’ by H.G. Wells; ‘Starship Troopers’ by Robert Heinlein; ‘Dune’ by Frank Herbert; ‘The Forever War’ by Joe Haldeman; ‘Ender’s Game’ by Orson Scott Card; and ‘Old Man’s War’ by John Scalzi

[2] Threat-casting is predicting potential threats in the range of 10-15 years, and then determining ways and means to avert, disrupt, or otherwise overcome those threats.

[3] As opposed to Clausewitz’s trinity of primordial violence, chance/probability, and rationality.

[4] Consider DeepMind’s with their AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero AIs, which could enable new avenues of invention.